Streaming

Calcite has extended SQL and relational algebra in order to support streaming queries.

- Introduction

- An example schema

- A simple query

- Filtering rows

- Projecting expressions

- Tumbling windows

- Tumbling windows, improved

- Hopping windows

- GROUPING SETS

- Filtering after aggregation

- Sub-queries, views and SQL’s closure property

- Converting between streams and relations

- The “pie chart” problem: Relational queries on streams

- Sorting

- Table constructor

- Sliding windows

- Cascading windows

- Joining streams to tables

- Joining streams to streams

- DML

- Punctuation

- State of the stream

- Functions

- References

Introduction

Streams are collections to records that flow continuously, and forever. Unlike tables, they are not typically stored on disk, but flow over the network and are held for short periods of time in memory.

Streams complement tables because they represent what is happening in the present and future of the enterprise whereas tables represent the past. It is very common for a stream to be archived into a table.

Like tables, you often want to query streams in a high-level language based on relational algebra, validated according to a schema, and optimized to take advantage of available resources and algorithms.

Calcite’s SQL is an extension to standard SQL, not another ‘SQL-like’ language. The distinction is important, for several reasons:

- Streaming SQL is easy to learn for anyone who knows regular SQL.

- The semantics are clear, because we aim to produce the same results on a stream as if the same data were in a table.

- You can write queries that combine streams and tables (or the history of a stream, which is basically an in-memory table).

- Lots of existing tools can generate standard SQL.

If you don’t use the STREAM keyword, you are back in regular

standard SQL.

An example schema

Our streaming SQL examples use the following schema:

-

Orders (rowtime, productId, orderId, units)- a stream and a table -

Products (rowtime, productId, name)- a table -

Shipments (rowtime, orderId)- a stream

A simple query

Let’s start with the simplest streaming query:

SELECT STREAM *

FROM Orders;

rowtime | productId | orderId | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

10:17:00 | 30 | 5 | 4

10:17:05 | 10 | 6 | 1

10:18:05 | 20 | 7 | 2

10:18:07 | 30 | 8 | 20

11:02:00 | 10 | 9 | 6

11:04:00 | 10 | 10 | 1

11:09:30 | 40 | 11 | 12

11:24:11 | 10 | 12 | 4This query reads all columns and rows from the Orders stream.

Like any streaming query, it never terminates. It outputs a record whenever

a record arrives in Orders.

Type Control-C to terminate the query.

The STREAM keyword is the main extension in streaming SQL. It tells the

system that you are interested in incoming orders, not existing ones. The query

SELECT *

FROM Orders;

rowtime | productId | orderId | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

08:30:00 | 10 | 1 | 3

08:45:10 | 20 | 2 | 1

09:12:21 | 10 | 3 | 10

09:27:44 | 30 | 4 | 2

4 records returned.is also valid, but will print out all existing orders and then terminate. We call it a relational query, as opposed to streaming. It has traditional SQL semantics.

Orders is special, in that it has both a stream and a table. If you try to run

a streaming query on a table, or a relational query on a stream, Calcite gives

an error:

SELECT * FROM Shipments;

ERROR: Cannot convert stream 'SHIPMENTS' to a table

SELECT STREAM * FROM Products;

ERROR: Cannot convert table 'PRODUCTS' to a streamFiltering rows

Just as in regular SQL, you use a WHERE clause to filter rows:

SELECT STREAM *

FROM Orders

WHERE units > 3;

rowtime | productId | orderId | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

10:17:00 | 30 | 5 | 4

10:18:07 | 30 | 8 | 20

11:02:00 | 10 | 9 | 6

11:09:30 | 40 | 11 | 12

11:24:11 | 10 | 12 | 4Projecting expressions

Use expressions in the SELECT clause to choose which columns to return or

compute expressions:

SELECT STREAM rowtime,

'An order for ' || units || ' '

|| CASE units WHEN 1 THEN 'unit' ELSE 'units' END

|| ' of product #' || productId AS description

FROM Orders;

rowtime | description

----------+---------------------------------------

10:17:00 | An order for 4 units of product #30

10:17:05 | An order for 1 unit of product #10

10:18:05 | An order for 2 units of product #20

10:18:07 | An order for 20 units of product #30

11:02:00 | An order by 6 units of product #10

11:04:00 | An order by 1 unit of product #10

11:09:30 | An order for 12 units of product #40

11:24:11 | An order by 4 units of product #10We recommend that you always include the rowtime column in the SELECT

clause. Having a sorted timestamp in each stream and streaming query makes it

possible to do advanced calculations later, such as GROUP BY and JOIN.

Tumbling windows

There are several ways to compute aggregate functions on streams. The differences are:

- How many rows come out for each row in?

- Does each incoming value appear in one total, or more?

- What defines the “window”, the set of rows that contribute to a given output row?

- Is the result a stream or a relation?

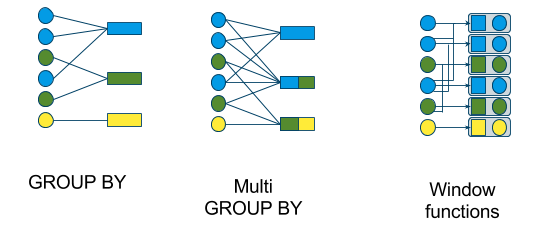

There are various window types:

- tumbling window (GROUP BY)

- hopping window (multi GROUP BY)

- sliding window (window functions)

- cascading window (window functions)

and the following diagram shows the kinds of query in which to use them:

First we’ll look a tumbling window, which is defined by a streaming

GROUP BY. Here is an example:

SELECT STREAM CEIL(rowtime TO HOUR) AS rowtime,

productId,

COUNT(*) AS c,

SUM(units) AS units

FROM Orders

GROUP BY CEIL(rowtime TO HOUR), productId;

rowtime | productId | c | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

11:00:00 | 30 | 2 | 24

11:00:00 | 10 | 1 | 1

11:00:00 | 20 | 1 | 7

12:00:00 | 10 | 3 | 11

12:00:00 | 40 | 1 | 12The result is a stream. At 11 o’clock, Calcite emits a sub-total for every

productId that had an order since 10 o’clock, timestamped 11 o’clock.

At 12 o’clock, it will emit

the orders that occurred between 11:00 and 12:00. Each input row contributes to

only one output row.

How did Calcite know that the 10:00:00 sub-totals were complete at 11:00:00,

so that it could emit them? It knows that rowtime is increasing, and it knows

that CEIL(rowtime TO HOUR) is also increasing. So, once it has seen a row

at or after 11:00:00, it will never see a row that will contribute to a 10:00:00

total.

A column or expression that is increasing or decreasing is said to be monotonic.

If column or expression has values that are slightly out of order, and the stream has a mechanism (such as punctuation or watermarks) to declare that a particular value will never be seen again, then the column or expression is said to be quasi-monotonic.

Without a monotonic or quasi-monotonic expression in the GROUP BY clause,

Calcite is

not able to make progress, and it will not allow the query:

SELECT STREAM productId,

COUNT(*) AS c,

SUM(units) AS units

FROM Orders

GROUP BY productId;

ERROR: Streaming aggregation requires at least one monotonic expression in GROUP BY clauseMonotonic and quasi-monotonic columns need to be declared in the schema.

The monotonicity is

enforced when records enter the stream and assumed by queries that read from

that stream. We recommend that you give each stream a timestamp column called

rowtime, but you can declare others to be monotonic, orderId, for example.

We discuss punctuation, watermarks, and other ways of making progress below.

Tumbling windows, improved

The previous example of tumbling windows was easy to write because the window

was one hour. For intervals that are not a whole time unit, say 2 hours or

2 hours and 17 minutes, you cannot use CEIL, and the expression gets more

complicated.

Calcite supports an alternative syntax for tumbling windows:

SELECT STREAM TUMBLE_END(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR) AS rowtime,

productId,

COUNT(*) AS c,

SUM(units) AS units

FROM Orders

GROUP BY TUMBLE(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR), productId;

rowtime | productId | c | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

11:00:00 | 30 | 2 | 24

11:00:00 | 10 | 1 | 1

11:00:00 | 20 | 1 | 7

12:00:00 | 10 | 3 | 11

12:00:00 | 40 | 1 | 12As you can see, it returns the same results as the previous query. The TUMBLE

function returns a grouping key that is the same for all the rows that will end

up in a given summary row; the TUMBLE_END function takes the same arguments

and returns the time at which that window ends;

there is also a TUMBLE_START function.

TUMBLE has an optional parameter to align the window.

In the following example,

we use a 30 minute interval and 0:12 as the alignment time,

so the query emits summaries at 12 and 42 minutes past each hour:

SELECT STREAM

TUMBLE_END(rowtime, INTERVAL '30' MINUTE, TIME '0:12') AS rowtime,

productId,

COUNT(*) AS c,

SUM(units) AS units

FROM Orders

GROUP BY TUMBLE(rowtime, INTERVAL '30' MINUTE, TIME '0:12'),

productId;

rowtime | productId | c | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

10:42:00 | 30 | 2 | 24

10:42:00 | 10 | 1 | 1

10:42:00 | 20 | 1 | 7

11:12:00 | 10 | 2 | 7

11:12:00 | 40 | 1 | 12

11:42:00 | 10 | 1 | 4Hopping windows

Hopping windows are a generalization of tumbling windows that allow data to be kept in a window for a longer than the emit interval.

For example, the following query emits a row timestamped 11:00 containing data from 08:00 to 11:00 (or 10:59.9 if we’re being pedantic), and a row timestamped 12:00 containing data from 09:00 to 12:00.

SELECT STREAM

HOP_END(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR, INTERVAL '3' HOUR) AS rowtime,

COUNT(*) AS c,

SUM(units) AS units

FROM Orders

GROUP BY HOP(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR, INTERVAL '3' HOUR);

rowtime | c | units

----------+----------+-------

11:00:00 | 4 | 27

12:00:00 | 8 | 50In this query, because the retain period is 3 times the emit period, every input

row contributes to exactly 3 output rows. Imagine that the HOP function

generates a collection of group keys for incoming row, and places its values

in the accumulators of each of those group keys. For example,

HOP(10:18:00, INTERVAL '1' HOUR, INTERVAL '3') generates 3 periods

[08:00, 09:00)

[09:00, 10:00)

[10:00, 11:00)

This raises the possibility of allowing user-defined partitioning functions

for users who are not happy with the built-in functions HOP and TUMBLE.

We can build complex complex expressions such as an exponentially decaying moving average:

SELECT STREAM HOP_END(rowtime),

productId,

SUM(unitPrice * EXP((rowtime - HOP_START(rowtime)) SECOND / INTERVAL '1' HOUR))

/ SUM(EXP((rowtime - HOP_START(rowtime)) SECOND / INTERVAL '1' HOUR))

FROM Orders

GROUP BY HOP(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' SECOND, INTERVAL '1' HOUR),

productIdEmits:

- a row at

11:00:00containing rows in[10:00:00, 11:00:00); - a row at

11:00:01containing rows in[10:00:01, 11:00:01).

The expression weighs recent orders more heavily than older orders. Extending the window from 1 hour to 2 hours or 1 year would have virtually no effect on the accuracy of the result (but use more memory and compute).

Note that we use HOP_START inside an aggregate function (SUM) because it

is a value that is constant for all rows within a sub-total. This

would not be allowed for typical aggregate functions (SUM, COUNT

etc.).

If you are familiar with GROUPING SETS, you may notice that partitioning

functions can be seen as a generalization of GROUPING SETS, in that they

allow an input row to contribute to multiple sub-totals.

The auxiliary functions for GROUPING SETS,

such as GROUPING() and GROUP_ID,

can be used inside aggregate functions, so it is not surprising that

HOP_START and HOP_END can be used in the same way.

GROUPING SETS

GROUPING SETS is valid for a streaming query provided that every

grouping set contains a monotonic or quasi-monotonic expression.

CUBE and ROLLUP are not valid for streaming query, because they will

produce at least one grouping set that aggregates everything (like

GROUP BY ()).

Filtering after aggregation

As in standard SQL, you can apply a HAVING clause to filter rows emitted by

a streaming GROUP BY:

SELECT STREAM TUMBLE_END(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR) AS rowtime,

productId

FROM Orders

GROUP BY TUMBLE(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR), productId

HAVING COUNT(*) > 2 OR SUM(units) > 10;

rowtime | productId

----------+-----------

10:00:00 | 30

11:00:00 | 10

11:00:00 | 40Sub-queries, views and SQL’s closure property

The previous HAVING query can be expressed using a WHERE clause on a

sub-query:

SELECT STREAM rowtime, productId

FROM (

SELECT TUMBLE_END(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR) AS rowtime,

productId,

COUNT(*) AS c,

SUM(units) AS su

FROM Orders

GROUP BY TUMBLE(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR), productId)

WHERE c > 2 OR su > 10;

rowtime | productId

----------+-----------

10:00:00 | 30

11:00:00 | 10

11:00:00 | 40HAVING was introduced in the early days of SQL, when a way was needed to

perform a filter after aggregation. (Recall that WHERE filters rows before

they enter the GROUP BY clause.)

Since then, SQL has become a mathematically closed language, which means that any operation you can perform on a table can also perform on a query.

The closure property of SQL is extremely powerful. Not only does it render

HAVING obsolete (or, at least, reduce it to syntactic sugar), it makes views

possible:

CREATE VIEW HourlyOrderTotals (rowtime, productId, c, su) AS

SELECT TUMBLE_END(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR),

productId,

COUNT(*),

SUM(units)

FROM Orders

GROUP BY TUMBLE(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR), productId;

SELECT STREAM rowtime, productId

FROM HourlyOrderTotals

WHERE c > 2 OR su > 10;

rowtime | productId

----------+-----------

10:00:00 | 30

11:00:00 | 10

11:00:00 | 40Sub-queries in the FROM clause are sometimes referred to as “inline views”,

but really, they are more fundamental than views. Views are just a convenient

way to carve your SQL into manageable chunks by giving the pieces names and

storing them in the metadata repository.

Many people find that nested queries and views are even more useful on streams than they are on relations. Streaming queries are pipelines of operators all running continuously, and often those pipelines get quite long. Nested queries and views help to express and manage those pipelines.

And, by the way, a WITH clause can accomplish the same as a sub-query or

a view:

WITH HourlyOrderTotals (rowtime, productId, c, su) AS (

SELECT TUMBLE_END(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR),

productId,

COUNT(*),

SUM(units)

FROM Orders

GROUP BY TUMBLE(rowtime, INTERVAL '1' HOUR), productId)

SELECT STREAM rowtime, productId

FROM HourlyOrderTotals

WHERE c > 2 OR su > 10;

rowtime | productId

----------+-----------

10:00:00 | 30

11:00:00 | 10

11:00:00 | 40Converting between streams and relations

Look back at the definition of the HourlyOrderTotals view.

Is the view a stream or a relation?

It does not contain the STREAM keyword, so it is a relation.

However, it is a relation that can be converted into a stream.

You can use it in both relational and streaming queries:

# A relation; will query the historic Orders table.

# Returns the largest number of product #10 ever sold in one hour.

SELECT max(su)

FROM HourlyOrderTotals

WHERE productId = 10;

# A stream; will query the Orders stream.

# Returns every hour in which at least one product #10 was sold.

SELECT STREAM rowtime

FROM HourlyOrderTotals

WHERE productId = 10;This approach is not limited to views and sub-queries.

Following the approach set out in CQL [1], every query

in streaming SQL is defined as a relational query and converted to a stream

using the STREAM keyword in the top-most SELECT.

If the STREAM keyword is present in sub-queries or view definitions, it has no

effect.

At query preparation time, Calcite figures out whether the relations referenced in the query can be converted to streams or historical relations.

Sometimes a stream makes available some of its history (say the last 24 hours of data in an Apache Kafka [2] topic) but not all. At run time, Calcite figures out whether there is sufficient history to run the query, and if not, gives an error.

The “pie chart” problem: Relational queries on streams

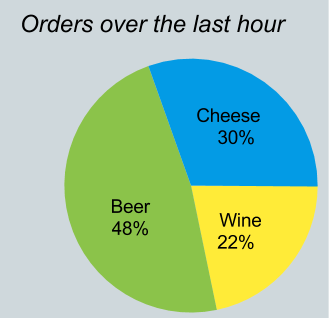

One particular case where you need to convert a stream to a relation occurs in what I call the “pie chart problem”. Imagine that you need to write a web page with a chart, like the following, that summarizes the number of orders for each product over the last hour.

But the Orders stream only contains a few records, not an hour’s summary.

We need to run a relational query on the history of the stream:

SELECT productId, count(*)

FROM Orders

WHERE rowtime BETWEEN current_timestamp - INTERVAL '1' HOUR

AND current_timestamp;If the history of the Orders stream is being spooled to the Orders table,

we can answer the query, albeit at a high cost. Better, if we can tell the

system to materialize one hour summary into a table,

maintain it continuously as the stream flows,

and automatically rewrite queries to use the table.

Sorting

The story for ORDER BY is similar to GROUP BY.

The syntax looks like regular SQL, but Calcite must be sure that it can deliver

timely results. It therefore requires a monotonic expression on the leading edge

of your ORDER BY key.

SELECT STREAM CEIL(rowtime TO hour) AS rowtime, productId, orderId, units

FROM Orders

ORDER BY CEIL(rowtime TO hour) ASC, units DESC;

rowtime | productId | orderId | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

10:00:00 | 30 | 8 | 20

10:00:00 | 30 | 5 | 4

10:00:00 | 20 | 7 | 2

10:00:00 | 10 | 6 | 1

11:00:00 | 40 | 11 | 12

11:00:00 | 10 | 9 | 6

11:00:00 | 10 | 12 | 4

11:00:00 | 10 | 10 | 1Most queries will return results in the order that they were inserted, because the engine is using streaming algorithms, but you should not rely on it. For example, consider this:

SELECT STREAM *

FROM Orders

WHERE productId = 10

UNION ALL

SELECT STREAM *

FROM Orders

WHERE productId = 30;

rowtime | productId | orderId | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

10:17:05 | 10 | 6 | 1

10:17:00 | 30 | 5 | 4

10:18:07 | 30 | 8 | 20

11:02:00 | 10 | 9 | 6

11:04:00 | 10 | 10 | 1

11:24:11 | 10 | 12 | 4The rows with productId = 30 are apparently out of order, probably because

the Orders stream was partitioned on productId and the partitioned streams

sent their data at different times.

If you require a particular ordering, add an explicit ORDER BY:

SELECT STREAM *

FROM Orders

WHERE productId = 10

UNION ALL

SELECT STREAM *

FROM Orders

WHERE productId = 30

ORDER BY rowtime;

rowtime | productId | orderId | units

----------+-----------+---------+-------

10:17:00 | 30 | 5 | 4

10:17:05 | 10 | 6 | 1

10:18:07 | 30 | 8 | 20

11:02:00 | 10 | 9 | 6

11:04:00 | 10 | 10 | 1

11:24:11 | 10 | 12 | 4Calcite will probably implement the UNION ALL by merging using rowtime,

which is only slightly less efficient.

You only need to add an ORDER BY to the outermost query. If you need to,

say, perform GROUP BY after a UNION ALL, Calcite will add an ORDER BY

implicitly, in order to make the GROUP BY algorithm possible.

Table constructor

The VALUES clause creates an inline table with a given set of rows.

Streaming is disallowed. The set of rows never changes, and therefore a stream would never return any rows.

> SELECT STREAM * FROM (VALUES (1, 'abc'));

ERROR: Cannot stream VALUESSliding windows

Standard SQL features so-called “analytic functions” that can be used in the

SELECT clause. Unlike GROUP BY, these do not collapse records. For each

record that goes in, one record comes out. But the aggregate function is based

on a window of many rows.

Let’s look at an example.

SELECT STREAM rowtime,

productId,

units,

SUM(units) OVER (ORDER BY rowtime RANGE INTERVAL '1' HOUR PRECEDING) unitsLastHour

FROM Orders;The feature packs a lot of power with little effort. You can have multiple

functions in the SELECT clause, based on multiple window specifications.

The following example returns orders whose average order size over the last 10 minutes is greater than the average order size for the last week.

SELECT STREAM *

FROM (

SELECT STREAM rowtime,

productId,

units,

AVG(units) OVER product (RANGE INTERVAL '10' MINUTE PRECEDING) AS m10,

AVG(units) OVER product (RANGE INTERVAL '7' DAY PRECEDING) AS d7

FROM Orders

WINDOW product AS (

ORDER BY rowtime

PARTITION BY productId))

WHERE m10 > d7;For conciseness, here we use a syntax where you partially define a window

using a WINDOW clause and then refine the window in each OVER clause.

You could also define all windows in the WINDOW clause, or all windows inline,

if you wish.

But the real power goes beyond syntax. Behind the scenes, this query is maintaining two tables, and adding and removing values from sub-totals using with FIFO queues. But you can access those tables without introducing a join into the query.

Some other features of the windowed aggregation syntax:

- You can define windows based on row count.

- The window can reference rows that have not yet arrived. (The stream will wait until they have arrived).

- You can compute order-dependent functions such as

RANKand median.

Cascading windows

What if we want a query that returns a result for every record, like a sliding window, but resets totals on a fixed time period, like a tumbling window? Such a pattern is called a cascading window. Here is an example:

SELECT STREAM rowtime,

productId,

units,

SUM(units) OVER (PARTITION BY FLOOR(rowtime TO HOUR)) AS unitsSinceTopOfHour

FROM Orders;It looks similar to a sliding window query, but the monotonic

expression occurs within the PARTITION BY clause of the window. As

the rowtime moves from from 10:59:59 to 11:00:00,

FLOOR(rowtime TO HOUR) changes from 10:00:00 to 11:00:00,

and therefore a new partition starts.

The first row to arrive in the new hour will start a

new total; the second row will have a total that consists of two rows,

and so on.

Calcite knows that the old partition will never be used again, so removes all sub-totals for that partition from its internal storage.

Analytic functions that using cascading and sliding windows can be combined in the same query.

Joining streams to tables

There are two kinds of join where streams are concerned: stream-to-table join and stream-to-stream join.

A stream-to-table join is straightforward if the contents of the table are not changing. This query enriches a stream of orders with each product’s list price:

SELECT STREAM o.rowtime, o.productId, o.orderId, o.units,

p.name, p.unitPrice

FROM Orders AS o

JOIN Products AS p

ON o.productId = p.productId;

rowtime | productId | orderId | units | name | unitPrice

----------+-----------+---------+-------+ -------+-----------

10:17:00 | 30 | 5 | 4 | Cheese | 17

10:17:05 | 10 | 6 | 1 | Beer | 0.25

10:18:05 | 20 | 7 | 2 | Wine | 6

10:18:07 | 30 | 8 | 20 | Cheese | 17

11:02:00 | 10 | 9 | 6 | Beer | 0.25

11:04:00 | 10 | 10 | 1 | Beer | 0.25

11:09:30 | 40 | 11 | 12 | Bread | 100

11:24:11 | 10 | 12 | 4 | Beer | 0.25What should happen if the table is changing? For example, suppose the unit price of product 10 is increased to 0.35 at 11:00. Orders placed before 11:00 should have the old price, and orders placed after 11:00 should reflect the new price.

One way to implement this is to have a table that keeps every version

with a start and end effective date, ProductVersions in the following

example:

SELECT STREAM *

FROM Orders AS o

JOIN ProductVersions AS p

ON o.productId = p.productId

AND o.rowtime BETWEEN p.startDate AND p.endDate

rowtime | productId | orderId | units | productId1 | name | unitPrice

----------+-----------+---------+-------+ -----------+--------+-----------

10:17:00 | 30 | 5 | 4 | 30 | Cheese | 17

10:17:05 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 10 | Beer | 0.25

10:18:05 | 20 | 7 | 2 | 20 | Wine | 6

10:18:07 | 30 | 8 | 20 | 30 | Cheese | 17

11:02:00 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 10 | Beer | 0.35

11:04:00 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 10 | Beer | 0.35

11:09:30 | 40 | 11 | 12 | 40 | Bread | 100

11:24:11 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 10 | Beer | 0.35The other way to implement this is to use a database with temporal support

(the ability to find the contents of the database as it was at any moment

in the past), and the system needs to know that the rowtime column of

the Orders stream corresponds to the transaction timestamp of the

Products table.

For many applications, it is not worth the cost and effort of temporal support or a versioned table. It is acceptable to the application that the query gives different results when replayed: in this example, on replay, all orders of product 10 are assigned the later unit price, 0.35.

Joining streams to streams

It makes sense to join two streams if the join condition somehow forces them to remain a finite distance from one another. In the following query, the ship date is within one hour of the order date:

SELECT STREAM o.rowtime, o.productId, o.orderId, s.rowtime AS shipTime

FROM Orders AS o

JOIN Shipments AS s

ON o.orderId = s.orderId

AND s.rowtime BETWEEN o.rowtime AND o.rowtime + INTERVAL '1' HOUR;

rowtime | productId | orderId | shipTime

----------+-----------+---------+----------

10:17:00 | 30 | 5 | 10:55:00

10:17:05 | 10 | 6 | 10:20:00

11:02:00 | 10 | 9 | 11:58:00

11:24:11 | 10 | 12 | 11:44:00Note that quite a few orders do not appear, because they did not ship within an hour. By the time the system receives order 10, timestamped 11:24:11, it has already removed orders up to and including order 8, timestamped 10:18:07, from its hash table.

As you can see, the “lock step”, tying together monotonic or quasi-monotonic columns of the two streams, is necessary for the system to make progress. It will refuse to execute a query if it cannot deduce a lock step.

DML

It’s not only queries that make sense against streams;

it also makes sense to run DML statements (INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE,

and also their rarer cousins UPSERT and REPLACE) against streams.

DML is useful because it allows you do materialize streams or tables based on streams, and therefore save effort when values are used often.

Consider how streaming applications often consist of pipelines of queries, each query transforming input stream(s) to output stream(s). The component of a pipeline can be a view:

CREATE VIEW LargeOrders AS

SELECT STREAM * FROM Orders WHERE units > 1000;or a standing INSERT statement:

INSERT INTO LargeOrders

SELECT STREAM * FROM Orders WHERE units > 1000;These look similar, and in both cases the next step(s) in the pipeline

can read from LargeOrders without worrying how it was populated.

There is a difference in efficiency: the INSERT statement does the

same work no matter how many consumers there are; the view does work

proportional to the number of consumers, and in particular, does no

work if there are no consumers.

Other forms of DML make sense for streams. For example, the following

standing UPSERT statement maintains a table that materializes a summary

of the last hour of orders:

UPSERT INTO OrdersSummary

SELECT STREAM productId,

COUNT(*) OVER lastHour AS c

FROM Orders

WINDOW lastHour AS (

PARTITION BY productId

ORDER BY rowtime

RANGE INTERVAL '1' HOUR PRECEDING)Punctuation

Punctuation[5] allows a stream query to make progress even if there are not enough values in a monotonic key to push the results out.

(I prefer the term “rowtime bounds”, and watermarks[6] are a related concept, but for these purposes, punctuation will suffice.)

If a stream has punctuation enabled then it may not be sorted but is nevertheless sortable. So, for the purposes of semantics, it is sufficient to work in terms of sorted streams.

By the way, an out-of-order stream is also sortable if it is t-sorted (i.e. every record is guaranteed to arrive within t seconds of its timestamp) or k-sorted (i.e. every record is guaranteed to be no more than k positions out of order). So queries on these streams can be planned similarly to queries on streams with punctuation.

And, we often want to aggregate over attributes that are not time-based but are nevertheless monotonic. “The number of times a team has shifted between winning-state and losing-state” is one such monotonic attribute. The system needs to figure out for itself that it is safe to aggregate over such an attribute; punctuation does not add any extra information.

I have in mind some metadata (cost metrics) for the planner:

- Is this stream sorted on a given attribute (or attributes)?

- Is it possible to sort the stream on a given attribute? (For finite relations, the answer is always “yes”; for streams it depends on the existence of punctuation, or linkage between the attributes and the sort key.)

- What latency do we need to introduce in order to perform that sort?

- What is the cost (in CPU, memory etc.) of performing that sort?

We already have (1), in BuiltInMetadata.Collation. For (2), the answer is always “true” for finite relations. But we’ll need to implement (2), (3) and (4) for streams.

State of the stream

Not all concepts in this article have been implemented in Calcite. And others may be implemented in Calcite but not in a particular adapter such as SamzaSQL [3] [4].

Implemented

- Streaming

SELECT,WHERE,GROUP BY,HAVING,UNION ALL,ORDER BY -

FLOORandCEILfunctions - Monotonicity

- Streaming

VALUESis disallowed

Not implemented

The following features are presented in this document as if Calcite supports them, but in fact it does not (yet). Full support means that the reference implementation supports the feature (including negative cases) and the TCK tests it.

- Stream-to-stream

JOIN - Stream-to-table

JOIN - Stream on view

- Streaming

UNION ALLwithORDER BY(merge) - Relational query on stream

- Streaming windowed aggregation (sliding and cascading windows)

- Check that

STREAMin sub-queries and views is ignored - Check that streaming

ORDER BYcannot haveOFFSETorLIMIT - Limited history; at run time, check that there is sufficient history to run the query.

- Quasi-monotonicity

-

HOPandTUMBLE(and auxiliaryHOP_START,HOP_END,TUMBLE_START,TUMBLE_END) functions

To do in this document

- Re-visit whether you can stream

VALUES -

OVERclause to define window on stream - Consider whether to allow

CUBEandROLLUPin streaming queries, with an understanding that some levels of aggregation will never complete (because they have no monotonic expressions) and thus will never be emitted. - Fix the

UPSERTexample to remove records for products that have not occurred in the last hour. - DML that outputs to multiple streams; perhaps an extension to the standard

REPLACEstatement.

Functions

The following functions are not present in standard SQL but are defined in streaming SQL.

Scalar functions:

-

FLOOR(dateTime TO intervalType)rounds a date, time or timestamp value down to a given interval type -

CEIL(dateTime TO intervalType)rounds a date, time or timestamp value up to a given interval type

Partitioning functions:

-

HOP(t, emit, retain)returns a collection of group keys for a row to be part of a hopping window -

HOP(t, emit, retain, align)returns a collection of group keys for a row to be part of a hopping window with a given alignment -

TUMBLE(t, emit)returns a group key for a row to be part of a tumbling window -

TUMBLE(t, emit, align)returns a group key for a row to be part of a tumbling window with a given alignment

TUMBLE(t, e) is equivalent to TUMBLE(t, e, TIME '00:00:00').

TUMBLE(t, e, a) is equivalent to HOP(t, e, e, a).

HOP(t, e, r) is equivalent to HOP(t, e, r, TIME '00:00:00').

References

- [1] Arvind Arasu, Shivnath Babu, and Jennifer Widom (2003) The CQL Continuous Query Language: Semantic Foundations and Query Execution.

- [2] Apache Kafka.

- [3] Apache Samza.

- [4] SamzaSQL.

- [5] Peter A. Tucker, David Maier, Tim Sheard, and Leonidas Fegaras (2003) Exploiting Punctuation Semantics in Continuous Data Streams.

- [6] Tyler Akidau, Alex Balikov, Kaya Bekiroglu, Slava Chernyak, Josh Haberman, Reuven Lax, Sam McVeety, Daniel Mills, Paul Nordstrom, and Sam Whittle (2013) MillWheel: Fault-Tolerant Stream Processing at Internet Scale.